In the Name of Love

Elites embrace the “do what you love” mantra. But it devalues work and hurts workers.

Photo courtesy Mario de Armas/design*sponge

“Do what you love. Love what you do.”

The command is framed and perched in a living room that can only be described as “well-curated.” A picture of this room appeared first on a popular design blog

and has been pinned, tumbl’d, and liked thousands of times. Though it

introduces exhortations to labor into a space of leisure, the “do what

you love” living room is the place all those pinners and likers long to

be.

There’s little doubt that “do what you love” (DWYL) is now the

unofficial work mantra for our time. The problem with DWYL, however, is

that it leads not to salvation but to the devaluation of actual work—and

more importantly, the dehumanization of the vast majority of laborers.

Superficially, DWYL is an uplifting piece of advice, urging us to

ponder what it is we most enjoy doing and then turn that activity into a

wage-generating enterprise. But why should our pleasure be for profit?

And who is the audience for this dictum?

DWYL is a secret handshake of the privileged and a worldview that

disguises its elitism as noble self-betterment. According to this way of

thinking, labor is not something one does for compensation but is an

act of love. If profit doesn’t happen to follow, presumably it is

because the worker’s passion and determination were insufficient. Its

real achievement is making workers believe their labor serves the self

and not the marketplace.

Aphorisms usually have numerous origins and reincarnations, but the nature of DWYL confounds precise attribution. Oxford Reference

links the phrase and variants of it to Martina Navratilova and François

Rabelais, among others. The Internet frequently attributes it to

Confucius, locating it in a misty, orientalized past. Oprah Winfrey and

other peddlers of positivity have included the notion in their

repertoires for decades. Even the world of finance has gotten in on

DWYL: “If you love what you do, it’s not ‘work,’” as the co-CEO of the private equity firm Carlyle Group put it to CNBC this week.

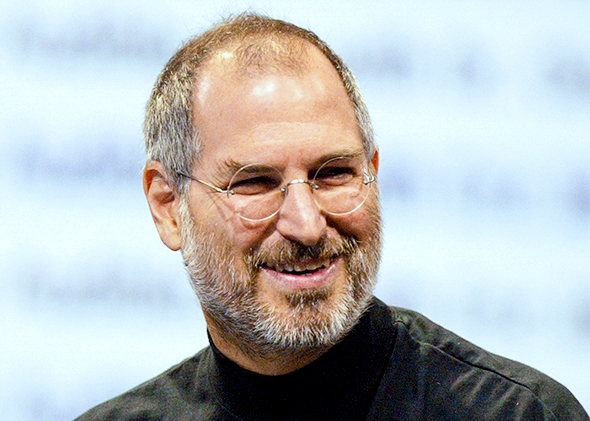

The most important recent evangelist of DWYL, however, was the late

Apple CEO Steve Jobs. In his graduation speech to the Stanford

University Class of 2005, Jobs recounted the creation of Apple and

inserted this reflection:

You’ve got to find what you love. And that is as true for your work as it is for your lovers. Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do.

In these four sentences, the words “you” and “your” appear eight

times. This focus on the individual isn’t surprising coming from Jobs,

who cultivated a very specific image of himself as a worker: inspired,

casual, passionate—all states agreeable with ideal romantic love. Jobs

conflated his besotted worker-self with his company so effectively that

his black turtleneck and jeans became metonyms for all of Apple and the

labor that maintains it.

Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

But by portraying Apple as a labor of his individual love, Jobs

elided the labor of untold thousands in Apple’s factories, hidden from

sight on the other side of the planet—the very labor that allowed Jobs

to actualize his love.

This erasure needs to be exposed. While DWYL seems harmless and

precious, it is self-focused to the point of narcissism. Jobs’

formulation of DWYL is the depressing antithesis to Henry David

Thoreau’s utopian vision of labor for all. In “Life Without Principle,”

Thoreau wrote:

… it would be good economy for a town to pay its laborers so well that they would not feel that they were working for low ends, as for a livelihood merely, but for scientific, even moral ends. Do not hire a man who does your work for money, but him who does it for the love of it.

Admittedly, Thoreau had little feel for the proletariat. (It’s hard

to imagine someone washing diapers for “scientific, even moral ends,” no

matter how well paid.) But he nonetheless maintains that society has a

stake in making work well compensated and meaningful. By contrast, the

21st-century Jobsian view asks us to turn inward. It absolves us of any obligation to, or acknowledgment of, the wider world.

One consequence of this isolation is the division that DWYL creates

among workers, largely along class lines. Work becomes divided into two

opposing classes: that which is lovable (creative, intellectual,

socially prestigious) and that which is not (repetitive, unintellectual,

undistinguished). Those in the lovable-work camp are vastly more

privileged in terms of wealth, social status, education, society’s

racial biases, and political clout, while comprising a small minority of

the workforce.

For those forced into unlovable work, it’s a different story. Under

the DWYL credo, labor that is done out of motives or needs other than

love—which is, in fact, most labor—is erased. As in Jobs’ Stanford

speech, unlovable but socially necessary work is banished from our

consciousness.

Think of the great variety of work that allowed Jobs to spend even

one day as CEO. His food harvested from fields, then transported across

great distances. His company’s goods assembled, packaged, shipped. Apple

advertisements scripted, cast, filmed. Lawsuits processed. Office

wastebaskets emptied and ink cartridges filled. Job creation goes both

ways. Yet with the vast majority of workers effectively invisible to

elites busy in their lovable occupations, how can it be surprising that

the heavy strains faced by today’s workers—abysmal wages, massive child

care costs, etc.—barely register as political issues even among the

liberal faction of the ruling class?

In ignoring most work and reclassifying the rest as love, DWYL may be

the most elegant anti-worker ideology around. Why should workers

assemble and assert their class interests if there’s no such thing as

work?

“Do what you love” disguises the fact that being able to choose a

career primarily for personal reward is a privilege, a sign of

socioeconomic class. Even if a self-employed graphic designer had

parents who could pay for art school and co-sign a lease for a slick

Brooklyn apartment, she can bestow DWYL as career advice upon those

covetous of her success.

If we believe that working as a Silicon Valley entrepreneur

or a museum publicist or a think-tank acolyte is essential to being true

to ourselves, what do we believe about the inner lives and hopes of those who clean hotel rooms and stock shelves at big-box stores? The answer is: nothing.

Yet arduous, low-wage work is what ever more Americans do

and will be doing. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the

two fastest-growing occupations projected

until 2020 are “personal care aide” and “home care aide,” with average

salaries in 2010 of $19,640 per year and $20,560 per year, respectively.

Elevating certain types of professions to something worthy of love

necessarily denigrates the labor of those who do unglamorous work that

keeps society functioning, especially the crucial work of caregivers.

If DWYL denigrates or makes dangerously invisible vast swaths of

labor that allow many of us to live in comfort and to do what we love,

it has also caused great damage to the professions it portends to

celebrate. Nowhere has the DWYL mantra been more devastating to its

adherents than in academia. The average Ph.D. student of the mid-2000s

forwent the easy money of finance and law (now slightly less easy) to

live on a meager stipend in order to pursue his passion for Norse

mythology or the history of Afro-Cuban music.

The reward for answering this higher calling is an academic employment marketplace in which about 41 percent of American faculty are adjunct professors—contract

instructors who usually receive low pay, no benefits, no office, no job

security, and no long-term stake in the schools where they work.

There are many factors that keep Ph.D.s providing such high-skilled labor for such low wages, including path dependency and the sunk costs of earning a Ph.D.,

but one of the strongest is how pervasively the DWYL doctrine is

embedded in academia. Few other professions fuse the personal identity

of their workers so intimately with the work output. Because academic

research should be done out of pure love, the actual conditions of and

compensation for this labor become afterthoughts, if they are considered

at all.

In “Academic Labor, the Aesthetics of Management, and the Promise of Autonomous Work,” Sarah Brouillette writes

of academic faculty, “[O]ur faith that our work offers non-material

rewards, and is more integral to our identity than a ‘regular’ job would

be, makes us ideal employees when the goal of management is to extract

our labor’s maximum value at minimum cost.”

Many academics like to think they have avoided a corporate work environment and its attendant values, but Marc Bousquet notes in his essay “We Work” that academia may actually provide a model for corporate management:

How to emulate the academic workplace and get people to work at a high level of intellectual and emotional intensity for fifty or sixty hours a week for bartenders’ wages or less? Is there any way we can get our employees to swoon over their desks, murmuring “I love what I do” in response to greater workloads and smaller paychecks? How can we get our workers to be like faculty and deny that they work at all? How can we adjust our corporate culture to resemble campus culture, so that our workforce will fall in love with their work too?

No one is arguing that enjoyable work should be less so. But

emotionally satisfying work is still work, and acknowledging it as such

doesn’t undermine it in any way. Refusing to acknowledge it, on the

other hand, opens the door to exploitation and harms all workers.

Ironically, DWYL reinforces exploitation even within the so-called

lovable professions, where off-the-clock, underpaid, or unpaid labor is

the new norm: reporters required to do the work of their laid-off photographers, publicists expected to pin and tweet on weekends, the 46 percent of the workforce

expected to check their work email on sick days. Nothing makes

exploitation go down easier than convincing workers that they are doing

what they love.

Instead of crafting a nation of self-fulfilled, happy workers, our

DWYL era has seen the rise of the adjunct professor and the unpaid

intern: people persuaded to work for cheap or free, or even for a net

loss of wealth. This has certainly been the case for all those interns

working for college credit or those who actually purchase

ultra-desirable fashion-house internships at auction. (Valentino and

Balenciaga are among a handful of houses that auctioned off monthlong internships. For charity, of course.) As an ongoing ProPublica investigation reveals, the unpaid intern is an ever-larger presence in the American workforce.

It should be no surprise that unpaid interns abound in fields that are highly socially desirable,

including fashion, media, and the arts. These industries have long been

accustomed to masses of employees willing to work for social currency

instead of actual wages, all in the name of love. Excluded from these

opportunities, of course, is the overwhelming majority of the

population: those who need to work for wages. This exclusion not only

calcifies economic and professional immobility, but it also insulates

these industries from the full diversity of voices society has to offer.

And it’s no coincidence that the industries that rely heavily on

interns—fashion, media, and the arts—just happen to be the feminized

ones, as Madeleine Schwartz wrote in Dissent.

Yet another damaging consequence of DWYL is how ruthlessly it works to

extract female labor for little or no compensation. Women comprise the

majority of the low-wage or unpaid workforce; as care workers, adjunct

faculty, and unpaid interns, they outnumber men. What unites all of this

work, whether performed by GEDs or Ph.D.s, is the belief that wages

shouldn’t be the primary motivation for doing it. Women are supposed to

do work because they are natural nurturers and are eager to please;

after all, they’ve been doing uncompensated child care, elder care, and

housework since time immemorial. And talking money is unladylike anyway.

Do what you love and you’ll never work a day in your life! Before

succumbing to the intoxicating warmth of that promise, it’s critical to

ask, “Who, exactly, benefits from making work feel like nonwork?” “Why should

workers feel as if they aren’t working when they are?” In masking the

very exploitative mechanisms of labor that it fuels, DWYL is, in fact,

the most perfect ideological tool of capitalism. If we acknowledged all

of our work as work, we could set appropriate limits for it, demanding

fair compensation and humane schedules that allow for family and leisure

time.

And if we did that, more of us could get around to doing what it is we really love.

No comments:

Post a Comment